This post was originally featured on Sharlynegger‘s blog, Coruscant Heights, and is reprinted with permission.

This is a topic I have always wanted to write about, mostly because I have seen so many analyses of Star Wars that did nothing but decry the near absence of women in the movies. As such, it’s often classified as one of the most sexist science-fiction works in existence, and let’s face it, there’s not even a need to run the Bechdel Test here.

Because we fail miserably.

However, as a woman who considers herself a feminist, I don’t think it’s fair to completely ignore the positive role Star Wars has had for women in science-fiction. I can say at least this: I was raised on Star Wars, literally – I saw the original movies at age four or five, I would cover my eyes per dad’s orders at the scary scenes (Honestly, call it instinct, I still do when the Emperor zaps Luke at the end of Return of the Jedi), I spent my entire childhood playing Star Wars video games with my father and pretending the office was a spaceship. After the Phantom Menace came out, I don’t think there was a day without my father referring to me as his “Young Padawan.”

And so, despite its lack of women, Star Wars had a huge influence on my life, and on my feminism, both the movies and the expanded universe. This is what I’m going to try to convince you of here, by having a closer look at every major female character in the movies.

Women in the Original Trilogy

Let’s start with the start; and I mean the real start. And I admit, it’s really difficult to find women in the Original Trilogy other than Leia. In all three movies, there are really three women that appear on screen and interact with the main characters: Princess Leia Organa, Mon Mothma, leader of the Rebellion, and Luke’s aunt, Beru Lars. But despite their small number, two of those had an extremely positive impact.

Princess Leia

Leia was, and still is the major female figure of Star Wars, and I believe things will stay that way for a long time.

She is a fascinating character: at first, she seems to fit all the medieval tropes of the Damsel in Distress (she is, after all, a princess) waiting for her knight to rescue her. Worse, that happens to her in all three movies: in A New Hope, Luke and Han rescue her from the Death Star; in The Empire Strikes Back, she is rescued by Lando’s men in Bespin’s Cloud City; finally, in Return of the Jedi, she finds herself in this situation twice, first in Jabba’s palace, and then on Endor when she is separated from the Rebel group.

“Again?!”

Seeing this, it’s easy to understand why, at first glance, Leia’s character wouldn’t strike anyone as a symbol of gender equality in science-fiction. But, let’s look at her a little closer. What is the first thing we learn about Princess Leia?

This scene.

Well, obviously, she is not just a princess; or at least not a very conventional one. Leia is presented to us as a spy, and a successful one too: she has an important mission, and she gets it done, at the cost of her safety and freedom. Her bravery in that scene is a trait that is something more often seen with male characters in similar movies.

On top of being introduced as a brave operative of the Rebellion, Leia’s resistance against Darth Vader shortly after immediately sets the mood: she is a force to be reckoned with. Later, we get more displays of her strength of character: she resists torture by the Empire, and still lies about the location of the Rebel base, even as her home planet is about to literally blown up. Furthermore, we see throughout all three movies that she is a strong, respected leader: displays of her command over her men are frequent.

I’m pretty sure they’re listening. Except the idiot who’s sleeping right there.

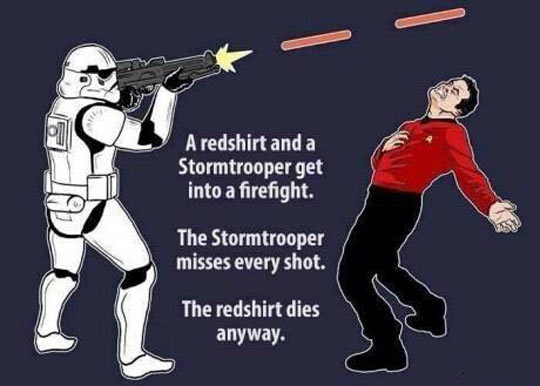

Leia’s skills don’t stop at politics and spying. She’s often shown as a very successful fighter (and a good shot).

I wouldn’t mess with her.

Let’s have a closer look at each of the situations where Leia had to be rescued.

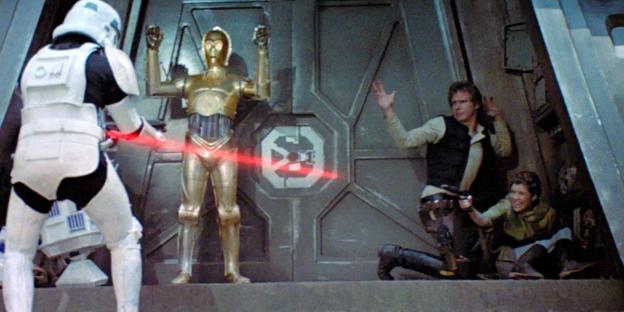

- In A New Hope, after being freed from her cell by Luke and Han (where she looks like she was just waiting in there completely bored, not very much in distress), Leia pretty much takes control of the situation. She is the one who throws everyone in the dumpster. Not Luke or Han, who are just sitting there unsure of what to do: no, Leia takes the blaster, shoots, and pretty much saves everyone’s butt (temporarily, at least).

- When on Bespin, despite being initially captured by the Empire and saved by Lando’s men, Leia, again, quickly takes control of the situation (with a little help from Chewbacca, I’ll admit). She is the one who saves Luke after his terrible first “Bring Your Son To Work” day.

- Return of the Jedi’s famous scene in Jabba The Hutt’s palace does not escape this treatment. Let’s not forget that Leia gets captured while rescuing Han – another middle finger to the Damsel in Distress trope. Of course, then Leia ends up in the infamous slave costume we all know (and I still think that was just George Lucas’ pervert side taking advantage of Carrie Fisher requesting new costumes). But then, what happens? Once again, Leia turns the situation around and literally strangles Jabba to death.

SHOW ME YER WARRIOR FACE

What else does that say about Leia? Well, we know that she literally doesn’t take anyone’s shit. Look at all this glorious sass.

Note: if anyone can find the author of these GIFs, so I can credit them, I’d be grateful!

In the end, I think Leia was my first role model. At the age I saw the movies, I was very much a Disney kid: all my princesses were Belle, Aurora, Cinderella-types. While those also have diverse qualities, Leia soon became my favorite princess. And here’s the key: Leia very much is a princess. But she’s also a fighter, a spy, a politician, and a leader. All those traits, usually associated with male characters, don’t make her any less of a princess, or any less of a woman. All at once, they have made her a very powerful, very influential woman in science-fiction.

Mon Mothma

Leia is not the only strong woman depicted in the original trilogy. How could one forget Mon Mothma? Her character, though very briefly seen in Return of the Jedi, is crucial. She is the leader of the Rebel Alliance, and she is seen giving the briefing before the Battle of Endor. Her role is even more important in the extended universe of Star Wars, with her making appearances as the “General Big Boss” in many games and books. Her iconic line “Many Bothans died to bring us this information” has long turned into a meme and ensured that her role in the movie did not get forgotten.

Representation matters. All power to the short brunettes! Ahem.

I think the most important thing about her is that her gender is never put into question in the movie: she is introduced, much like Leia, as a respected leader with a position important enough to command the entire Alliance.

Again, it’s only a shame that her appearance is so short; it reduces the importance and positivity of her character.

Aunt Beru and the others

Let’s be honest: the other female characters shown in the original movies are probably contributing to the whole “Star Wars is sexist” conclusion. And frankly, I don’t think they could be much worse.

Aunt Beru, the only woman who gets a name aside from Leia and Mon Mothma, is only used as emotional advancement for Luke, along with his uncle. She fits the role of the gentle mother figure who dies to make the male protagonist motivated enough to start his quest – something that is repeated in the prequels. The only thing that softens this up for her is that she dies along with Luke’s uncle, lessening the “Woman In the Refrigerator” trope effect (but don’t worry, we get that *twice* in the prequels! Yay!)

Aside from Beru, what do we have? The dancers in Jabba’s palace, which are your classic female characters in the background, and…the deleted Rebel pilots. Yes, you’ve read correctly: there were initially female X-wing pilots in Return of the Jedi, that is, before George Lucas scratched their parts at the last minute.

Wait, what?!

Some of them can be seen in the BluRay edition deleted scenes. Which raises the question: why were these scenes deleted at the last moment? Why was the footage not included? And why specifically the scenes including female pilots? Honestly, we may never know, but personally, I’ve got a pretty good idea. Maybe George Lucas offered them to fly in iron bikinis.

Women in the Prequels

That gives us two very positive roles for women in the old trilogy, but a distinct lack of named female characters, two of which were willingly removed from the movies. Mixed feelings, right? What about the prequels?

What we can observe from the prequels is that they are more recent, and there was a visible effort to include more women roles. But are those roles as positive as Leia and Mon Mothma? I’m not so sure. Again, there are only two major female characters in the prequels: Anakin’s mother, Shmi Skywalker, and Padmé Amidala. And if we compare these to Leia and Mon Mothma… well. See for yourself.

Shmi Skywalker

While I loved the gentleness and diversity in female personalities that Shmi represented for the Star Wars series, her entire character is a living trope. Her role was not quite as bad during the Phantom Menace, where she was even shown as a selfless, strong mother who put the wellbeing of her child in front of everything else – a common theme in fiction, but new to Star Wars – and was not afraid of living the rest of her life as a slave.

“Oh, sweetheart, of *course* we’re going to see each other again. After all, someone has to die in your arms to make you all dark and stuff.”

Then, Attack of the Clones happens. Shmi then turns into the perfect embodiment of the Woman in the Refrigerator I was mentioning earlier: she is only a reason for Anakin to start turning to the Dark Side. Just like that, we learn that her entire existence, her entire character is only there for Anakin’s character development. Quite frankly, she is not really the positive woman representation I was looking for. What else do we have in the prequels?

Padmé Amidala

Padmé – pardon me, Queen Amidala – started out wonderfully well. She is introduced as a powerful queen, loved by her people, and most importantly, elected. As such, Padmé’s position does not come from only “tradition”: she is a young prodigy who earned her place. Much like Leia, she is shown as a fiery woman and expert politician, with battle skills and a natural talent for leadership.

I remember having a lot more pimples at 14.

During most of The Phantom Menace, she is portrayed as clever, gentle, and willing to put herself at risk for her people. All very good traits. Still, like Leia, she still very much a woman, and that is a good thing! Women can be strong AND intelligent AND pretty. AND like beautifully crafted costumes. Attack of the Clones, despite what one might think, did not ruin her character right away: we get to see more of her fighting skills, and meet her strong-headed side, the side that refuses to be seduced right away by Anakin as she focuses on her career.

Sadly, that doesn’t last. Quickly, Anakin and Padmé’s romance, unlike Leia and Han’s, becomes central to the story: Padmé is still a strong ally, but that is when we start seeing where the prequels are heading with her.

I mean, let’s face it, she was pretty badass in Attack of the Clones.

I had doubts when I saw the movie, but even then, I still considered her a powerful, positive character. Even during her wedding with Anakin, even though it made little sense. It was certainly saddening to see her relinquish her role as a politician to that of “forbidden love character”. But I don’t think anything could have prepared me for Revenge of the Sith when it comes to her personality.

I mean – what happened? Forget Padmé’s leadership skills, forget her politician background. Revenge of the Sith turns her into a plot hole (because, frankly, why does Leia remember her if she died giving birth to her?) The bridge to the original movies is sealed with her losing all interest as a character: she becomes nothing but Anakin’s character development, much like Shmi. Then again, we kind of all wish Anakin’s character development was actually a development.

I mean, WHO wrote this?

Padmé’s character becomes just terrible in that movie: she does nothing to save herself, or even to help Anakin. She just, literally, sits there during the entire movie waiting to be killed, while Anakin turns to the Dark Side to save her. The worst part of it is probably her “losing the will to live” at the end. Why would she lose the will to live? She is about to give birth to two perfectly healthy children, both of which could have been her only hope to save Anakin and the Jedi Order. Padmé, the Queen who got elected at the age of fourteen, the Senator who fought in a Geonosis arena, decides to simply let go of herself and her children because her lover needs to become Lord Vader by strangling her.

They did what to my character?

If you still think that makes sense, feel free to explain it to me. Because all I remember from that is this:

No matter what I do, I can still *hear it*

In the end, that gave me a very negative view of Padmé. The one character that I thought was going to be as inspiring as Leia turned out to be a plot-hole with no personality by the end of the prequels.

Sidenote: if you really think a politician as experienced and talented as Padmé would have chosen Jar-Jar Binks to represent her at the Senate while she was away, you… no. Just no.

A note on the background women

That said, it would be unfair to forget the other women presented in the prequels. Although none of them get a major role (at the exception, perhaps, of the assassin Zam), there are distinctively more than there were in the original trilogy.

We get to see a few female Jedi, including the librarian in the Jedi Temple. Finally, women with lightsabers! My days of running around the yard calling my dog Chewbacca and pretending to be a Jedi are validated.

Zam Wesell, the shapeshifting assassin in Attack of the Clones, is the first female villain we see in the movies. That fact makes her worth mentioning, and it is indeed nice to see more diverse profiles for female characters.

Zam was pretty cool, when you think about it.

Finally, Padmé’s all-female handmaiden crew, one of which dies for her in Attack of the Clones, are in my opinion another interesting female input in the series. It’s a shame they are not developed a little more. Despite the fact that they fit the traditional handmaiden mold, their devotion and courage to their queen sets them a little above that trope.

I think we’re done with the women that show up in the prequels. Not a very good score, either.

So, is Star Wars sexist?

With all that’s been said, I think it’s fair to say that Star Wars could use a few more women roles. It would have been nice to see more relevant female Jedi who get more than just a death scene (I’m looking at you, Aayla Secura), it would have been nice to see those female X-wing pilots included in the original movie. And, while I’m at it, why not show female Imperial officers?

The extended universe took on all of that. The contrast is stunning: the games, books and comics are filled with example of very diverse female characters. We have villains, Sith, Jedi, Imperials, pilots and bounty hunters of various races, whose gender is rarely ever called into question. When it comes to the representation, the extended universe certainly wins.

However, I don’t think we can say that the movies are doing so bad: both the original trilogy and the prequels showed strong women in positions of power. But that is where the prequels fail at having an impact as important as the original: Leia and Mon Mothma’s influence was never defined by their gender, and the romance in the original trilogy was only a side plot. In the prequels, while there are more women in the background, the romance is completely central to the plot, obfuscating the genderless qualities of Padmé. Worse, both of the major female characters are character development material for Anakin. As always, we are brought to the final conclusion that the original trilogy is better than the prequels.

Yes, I just went there.

In all seriousness: yes, the original trilogy definitely lacked women. But the positive representation that Leia generated by herself, with her personality, power, and story, had such an impact on the viewers that I think it’s still fair to call her a feminist heroine.

In any case, I can finally call her my favorite Disney princess.