Today’s guest post comes from Scott Weiner, a Ph.D student in political science at George Washington University. He writes on state-tribe relations, ethnic politics, and the game theory behind Carly Rae Jepsen songs.

Spoilerplate Warning

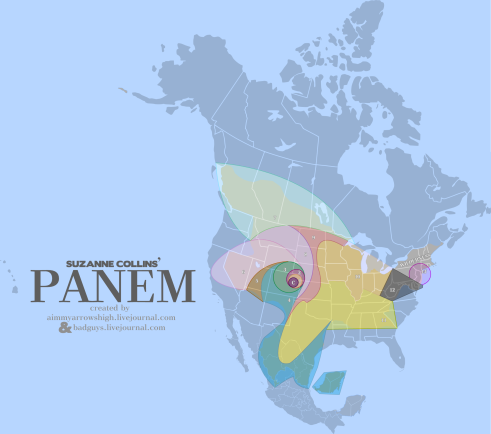

A map of Panem by AimArrowsHigh

The Hunger Games trilogy presents a case study of revolution which is on the one hand instructive and on the other hand puzzling. The state of Panem (post-apocalyptic America) experiences a revolution that shares both uncanny similarities and unmistakable differences with other revolutions, fictional and non-fictional. At the center of the revolution in Panem is the heroine of the series, a teenager by the name of Katniss Everdeen, who is played in the film version of The Hunger Games by actress Jennifer Lawrence. To Western audiences, Katniss Everdeen is the epitome of a revolutionary leader. However, a critical examination of the society of Panem and its revolution should raise serious questions in this regard. While many Westerners view Katniss Everdeen as empowered heroine, a critical comparison of her actions reveals deeply troubling attitudes and beliefs at play.

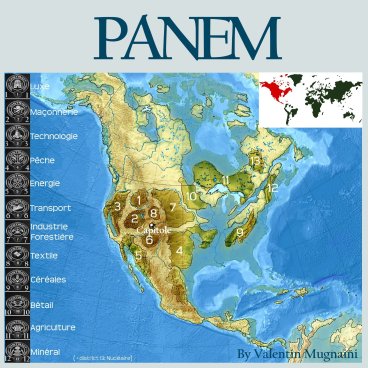

A fan-made map of Panem by Helmet 31

Flaws In The Revolutionary Account

The events which take place in Panem are uncritically accepted by many as a “revolution.” However, several aspects of these events throw this claim into doubt, particularly in light of scholarly accounts of the phenomenon.

First, the uprisings in Panem are exclusively by lower-class populations. Yet Barrington Moore (1966) underscores the importance of the “landed upper class” to revolution. It is of course possible that a landed upper class exists in the Capital, but accounts make no mention of this class defecting during the rebellion. While individuals with personal ties to Katniss Everdeen make efforts on her behalf, the major force of the uprising is from the peasantry. Moore predicts than in such cases the outcome of the revolution will be fascism. However, Panem lacks the privatized corporations which would be necessary for this outcome to occur.

Perhaps then the revolutions are a case of peasant rebellion a la James C. Scott (1976). This account too is incomplete. Peasant rebellion and the “everyday resistance” Scott writes about – criminal activity committed in defiance of the State – is usually confined to the periphery. In Panem, the population is reacting to national-level events in a national uprising whose goal is the downfall of the regime. These uprisings are also largely separate from the insurgency itself, comprised of what Bueno de Mesquita et al (2004) refer to as the “minimum winning coalition” or inner circle of the regime.

Finally, the source of the insurgency is not what existing accounts of revolution predict. Humiliation is often a key variable in a person’s decision to rebel. Additionally, Ted Robert Gurr (1970) identifies the role of relative deprivation in sparking a person to rebel. He argues that it is those underprivileged members of society who interact daily with the advantaged group who feel most painfully their own oppression. However, were this the case in Panem, the instigators of the rebellion should have been the Avoxes, criminals who have had their tongues removed by the State and serve as a source of domestic and municipal labor. True, the actual instigators – former winners of the Hunger Games – faced relative deprivation upon their arrival to the Capital. However, the Avoxes experienced the humiliation of this power differential much more sharply. While the lack of civil society in Panem may be partially to blame, it is more than conceivable that Avoxes should have at least participated in the rebellion once news of it came to the Capital.

Ultimately, the revolutionary account cannot explain the puzzling dynamics of the overthrow of President Snow in Panem. To better understand the uprisings there, we must ask why this is the case. A critical perspective is most instructive in this regard.

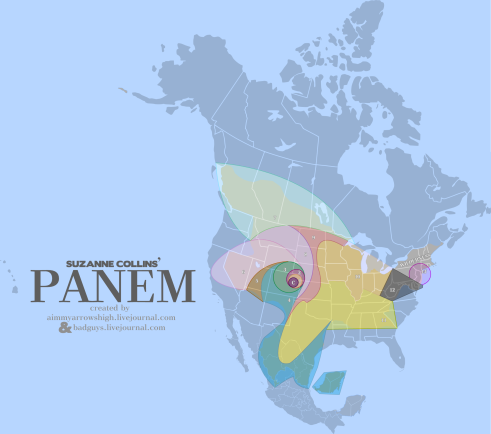

A fan-made map of Panem by Vamg

The Post-Orientalist Explanation

The Hunger Games revolves around the heroine Katniss Everdeen. Everdeen is an strong, empowered, individualistic minority member of society. In this regard, she represents the Liberal ideal type. Liberalism has its roots in the 19th century as a European ideology stressing individual empowerment for the benefit of society as a whole. Everdeen’s credentials as a liberal are established during the Hunger Games themselves. Everdeen’s reluctance to kill, her alliance with Rue, and her compassion after Rue’s death all speak to liberal notions of empowering the self, benefiting the social benefit of all. Her decision to convince Peeta to swallow nightlock – even though they were eventually stopped from doing so – is the ultimate act of self-empowerment and cooperation. As a result, Everdeen is touted later by the rebellion as the epitome of Liberalism. However, critical examination reveals that Everdeen’s actions are anything but empowering to her victims.

Liberalism as an ideology has also been used to justify violence and subjugation of non-liberal societies, often under the pretense of “humanitarian intervention” (Duffield, 2001). Katniss Everdeen is an empowered girl, but invokes the ways the Capital limited citizens’ rights in Panem as the pretense for violence against the State and its citizens. Her nickname is “Mockingjay,” a reference to genetically altered birds in Panem which can remember and mimic complex sound patterns. However, the nickname refers to Everdeen’s role as one who travels throughout Panem, diffusing her ideology and “enlightening” the citizenry. At the same time District 2’s citizens are supposedly being liberated, Everdeen is complicit in an attack in which citizens are killed – a paternalistic exercise of her own empowerment. Additionally, when the revolution’s leaders take a vote on whether the children of the Capital should be forced to participate in a Hunger Games of their own, Everdeen votes yes. The democratic nature of this proceeding should not distract from its decidedly illiberal leanings.

In a sense, Katniss Everdeen is an post-apocalyptic Lawrence of Arabia. Critical scholars understand the political role played by Lawrence of Arabia and other Westerners who visited the region as part of the ideology of Orientalism (Said, 1979). Orientalism is the idea that Western beliefs and attitudes of superiority towards the Middle East legitimized its domination of that region. Katniss Everdeen is an orientalist for a time after Orientalism – a Post-Orientalist. Her travels are not “liberating” for Panem’s citizens but rather preserve her own superiority over them. As one who created Liberal cooperation in the state of nature which is the Hunger Games, Everdeen flaunts her credentials for personal gain. Her aim is not to liberate the citizens of Panem but to use Liberalism as a cynical cover for her aims of national domination.

~

For further reading on the political science of the Hunger Games from Duck of Minerva, please see here and here.